Where'd all the time go?

What slow games, quiet platforms, and weekly rituals can teach us about time

Note:

I’m still figuring out what writing in public is supposed to feel like. Right now, I feel a little buttoned up here, more like I'm explaining than actually processing. I’m also trying to get better at condensing research. It’s hard, because there is just too much cool work out there!

I also hope to someday write here like I do in my group chats: stream of consciousness, slightly unhinged, terminally online… but authentically me.

Thanks for being here while I figure it all out.

Let’s get into part two of the series: This is Your Brain on Content.

I’m always feeling like I’m short on time.

Sometimes I have to look at my calendar or screen time just to remind myself that it was all accounted for: meetings, doctor’s appointments, errands, texts, social outings, media consumption.

Still, the day feels unanchored. It happened. I guess.

But if you asked me what it felt like, I’m not sure I could say.

I’ve been thinking about this feeling for a while, and it reminds me of a campy concept album from one of my favorite bands..

Time by Electric Light Orchestra, released in 1981, is written from the perspective of a man from the eighties who wakes up in the year 2095. He finds a shiny, technologically advanced world overflowing with information overload, loneliness, artificial pleasures, and fake memories and all he wants to do is go home.

The record is fun and theatrical and, strangely, one of the better metaphors I’ve found for the awful disorientation that creeps in after too many days full of screens.

Some days, we’re all that guy from the eighties, stuck in a future that moves too fast and means too little.

I tried to make sense of this feeling, to understand where all my time goes when I can't remember giving it away.

Felt time isn’t clock time

Psychologist Ruth Ogden studied time perception during the pandemic1 and found striking differences across countries, age groups, and emotional states.

In Iraq, people felt time slow down while in the UK, half of respondents said it sped up. In Argentina, young and physically active women felt time pass faster than older men.

She theorized that these differences stem from environmental factors like growing up in war zones or living under stricter lockdowns.

“We’re aware of the fragility of time,” she said. “We’re aware of what happens when your time to do the things you want is taken away from you.”

When the usual routines of life fall apart, so does our ability to keep track of time in the ways we expect.

Sociologists at Baylor call this sensation “multifaceted time disorientation.” Their research2 found that when people felt like time no longer followed expected rhythms, they reported more anxiety, depression, and loss of agency.

It makes sense. If nothing feels real enough to hold onto, it’s easy to unravel and lose control of your days.

Neurologically speaking, it’s interesting too: there is no single clock in the brain.

Different regions associated with memory, emotion, reward, and movement all track time in their own ways.

As Harvard neurologist Ed Miyawaki puts it:

“The idea that time is just one monolithic thing is just wrong.”

The signals we need to feel time

A 2022 paper3 proposed that human cognition uses two distinct systems for processing time:

a fast, intuitive system that tracks ongoing changes

and a slower, reflective system that reasons about time.

Building on that idea, it makes sense that we rely on a mix of contextual signals to situate ourselves in time. This could look like:

Performance-related feedback (How did I do? Was something completed or achieved?)

Sensory/ambient cues (What does this moment feel like? What shifted around me?)

Temporal boundaries (How much time has passed? What broke the flow and created a new scene?)

These signals help us separate one experience from the next and build narratives we can actually store in memory.

Without transitions, shifts, or endings, it becomes harder to differentiate one moment from another.

When we create digital content without thinking about how someone experiences the time they spend with it, we risk creating something ultimately forgettable.

Animal Crossing: A gentle structure during a disorienting time

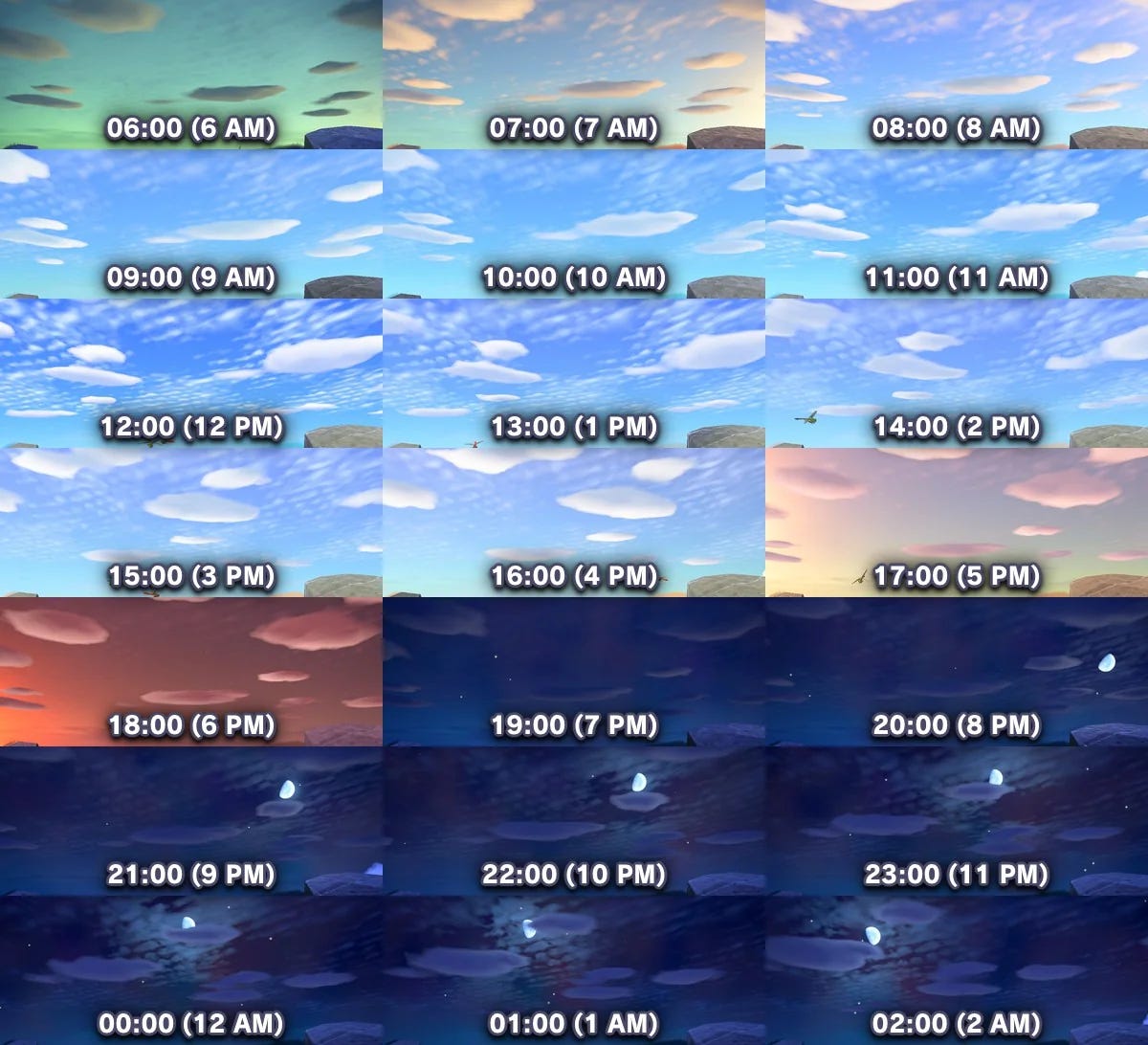

During the first wave of lockdowns in March 2020, Animal Crossing: New Horizons became a cultural obsession. With external routines collapsing, the game offered something steady and dependable, especially because it runs in real time.

Stores closed at night, seasons changed slowly, the sky darkened according to the player’s timezone.

The game embodied the three signals I suggested earlier:

Performance-related feedback: Catching a rare fish or completing a villager task gave immediate feedback and a sense of completion, acting as subtle event boundaries.

Sensory/ambient cues: Shifts in lighting, haptic feedback, consistent music, and the villagers’ gibberish speech acted as sensory anchors.

Temporal boundaries: Players had to wait for the sun to rise, for Tom Nook to open his shop, and for specific seasonal events to unfold which tied them to real-world rhythms.

The game also allowed social visits to player islands, a wildly popular feature during isolation. This can also provide context and help enforce time. Especially when celebrities like Elijah Wood visit your island:

Animal Crossing reminds me that content can be something to move through and feel inside of. That not everything needs to accelerate or maximize and some things can simply... unfold.

Flow vs. Drift

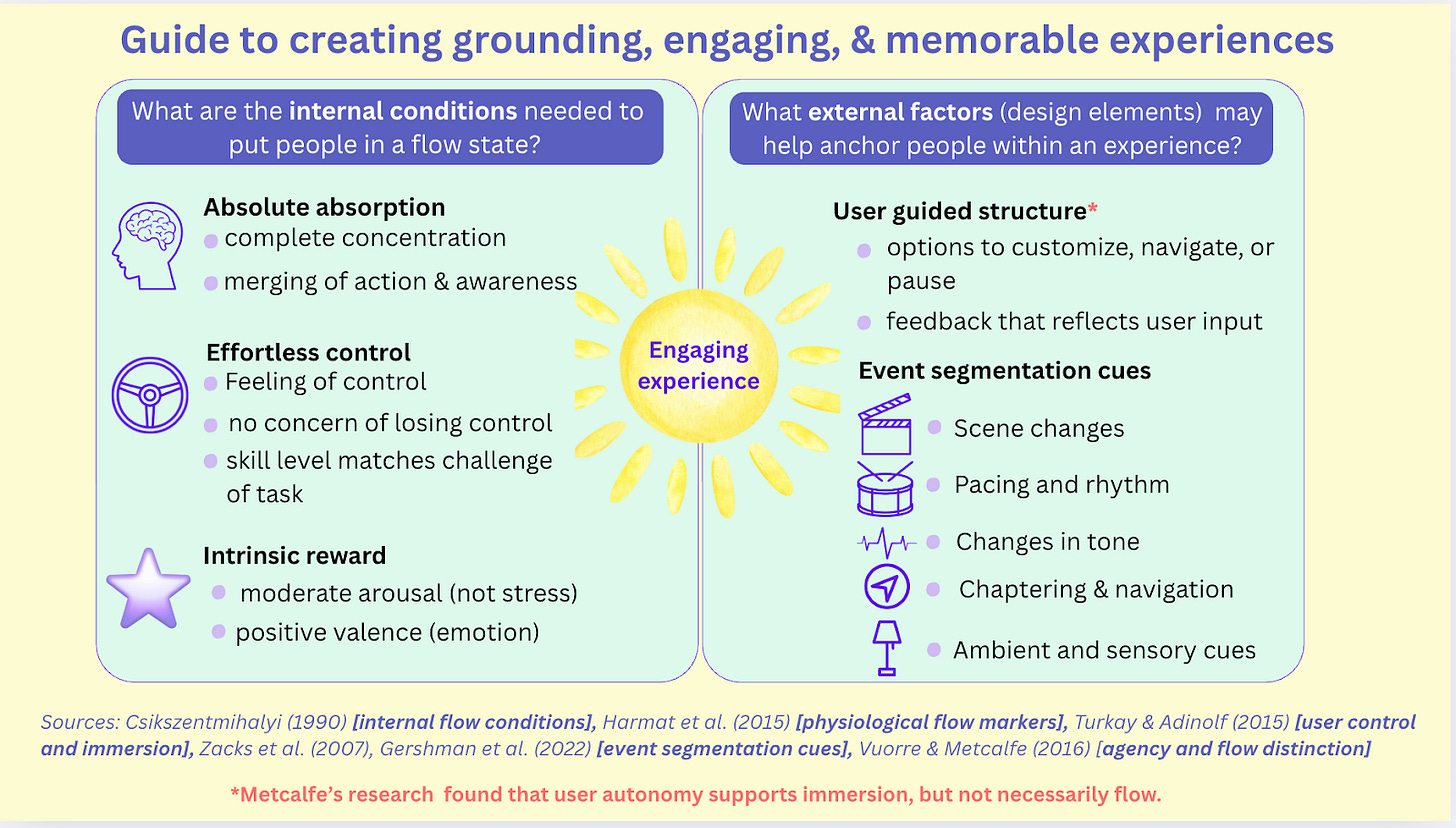

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who coined the term flow4, identified a set of internal conditions needed to enter that state. But what’s often overlooked is the role of environment and interface in helping those conditions emerge.

Flow is the feeling of full attention, being in the middle of something and not wanting to check your phone. Drift is what happens when you look up and realize you’ve spent the last hour scrolling, barely absorbing any of it.

For an experience to feel meaningful (and for time spent in it to feel meaningful) people need to feel like they have a say in it.

In digital environments, agency often comes down to small design choices: letting people pace themselves, adjust structure, or customize how feedback is delivered.

I put together a guide that summarizes Csíkszentmihályi’s findings on the internal conditions for flow, as well as research on environmental factors that can help encourage them.

Applying these learnings to digital products means asking different questions during design reviews:

Are we providing clear feedback loops for user actions?

Have we built in natural segmentation points, or are we optimizing for endless use?

How do we give people control over their own experience?

What can we do to help them remember it?

I think it is important to think about all of this because if you and your team are working hard to ship something, you want it to stay in the user's memory, not become another additional noise in their day.

Are.na: A digital tool that puts me in flow

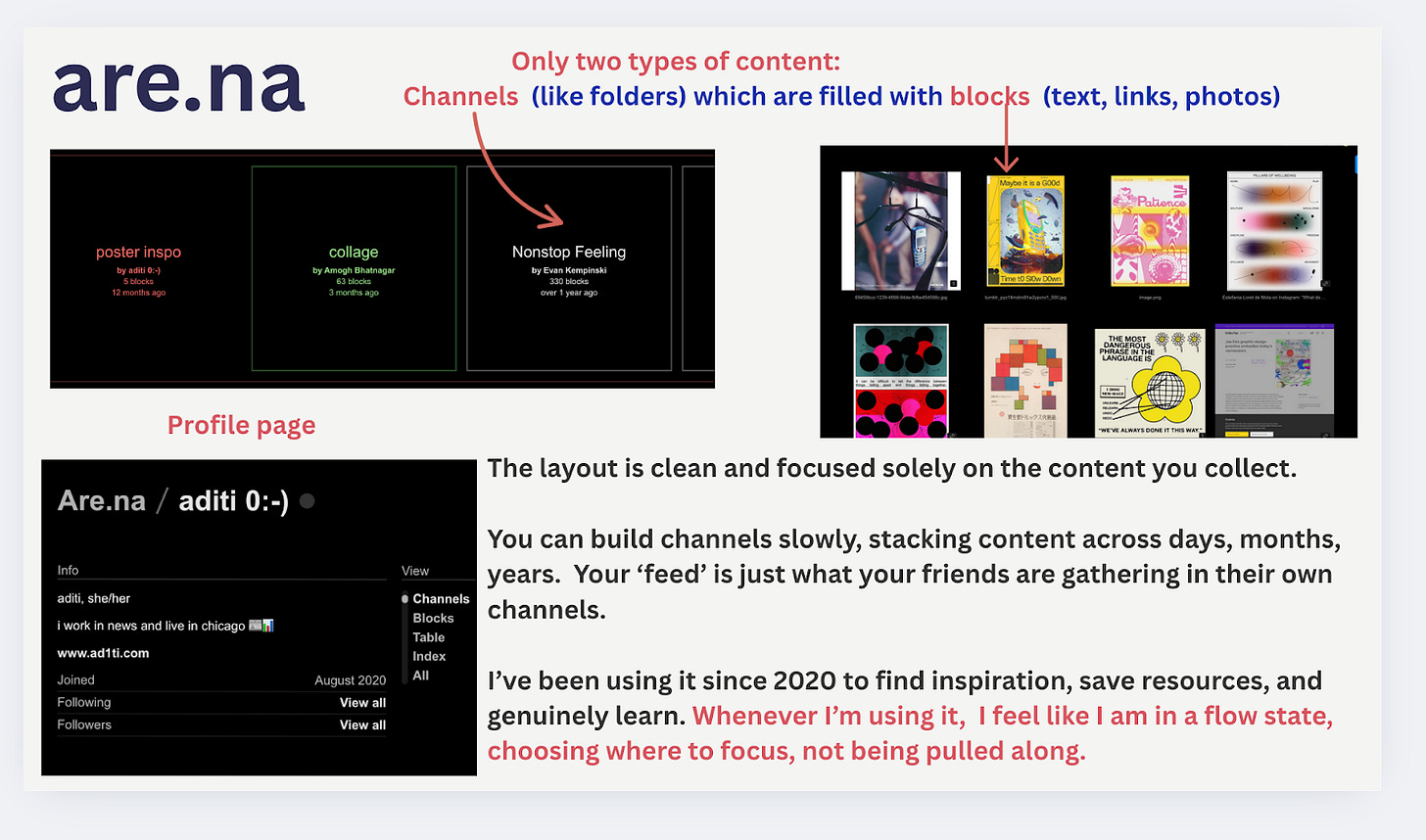

I wanted to find examples of digital spaces that didn’t leave me feeling like I’d just lost an hour to the void. Are.na came to mind.

Are.na describes itself as “a mindful space to work through ideas over time.” It’s one of the only platforms I use that doesn’t feel like it’s chasing me. I can actually enter a flow state while using it.

The focus is purely on the digital objects you collect. While you can see what your friends are collecting, it doesn’t feel performative or overstimulating. Sometimes what they find inspires you, and you might add it to your own channel. It feels slow, intentional, a break from the rest of the internet.

There’s so much to learn from the design of the site too: No algorithmic sorting, no loud notifications, neutral colors, white space used deliberately to reduce cognitive load.

The removal or minimization of “engagement” features can actually increase meaningful interaction, or at least, it does for me.

The structure time needs

I have a theory: event segmentation might help explain why weekly TV releases generate more cultural staying power than binge drops.

When The Pitt or Severance dropped weekly, each episode became an event: a marker in time, something to anticipate and then process.

Psychologist Jeffrey Zacks, who studies5 how we break continuous experience into scenes, has found that people naturally mark transitions, even during simple tasks like making breakfast. A shift in setting, a pause, a change in tone: these become event boundaries. They’re what we hold onto in our memory. He calls this event segmentation.

Without boundaries between events, the resulting experience is forgettable, disorienting.

In the physical world, it’s easier to mark time: You walk into another room, the light changes. Maybe there are new smells, sounds, and people.

But online, especially inside digital feeds and endless loops, you can scroll through 50 clips without a single break. Everything is the same and nothing marks one moment from the next.

When I was watching The Pitt, the Thursday night release schedule became an event boundary for me and many others.

Designing for memory, not just consumption

Anyone who creates or distributes information digitally should recognize: you’re shaping people’s experience of time, maybe even manipulating it.

What might happen if your next product planning session started by identifying memory points along user journeys? What if your KPIs included “experiences users can recall a week later” alongside traditional engagement metrics?

You could measure it in small ways:

A simple follow-up system showing users thumbnails of previously viewed vs. new content, a quick “memory persistence” check.

Microsurveys 24 hours, a week, a month after engagement, asking users what they remember.

A/B testing content with intentional cognitive “speed bumps” like chapters, summaries, or reflective pauses, to test for deeper engagement over time.

What kind of time does your work create?

Does your audience leave feeling more grounded, or more knocked off center?

What would your product or content feel like if people walked away not just entertained or informed, but with a deeper sense of where they were, when they were, who they were?

Given the rise in news fatigue (especially among younger audiences) I think a lot of journalism orgs already have their answer…

Have you ever come across a digital space that made you feel time differently? I’d love to hear about it.

Thanks for spending a little time here with me, and for reading part two of This Is Your Brain on Content.

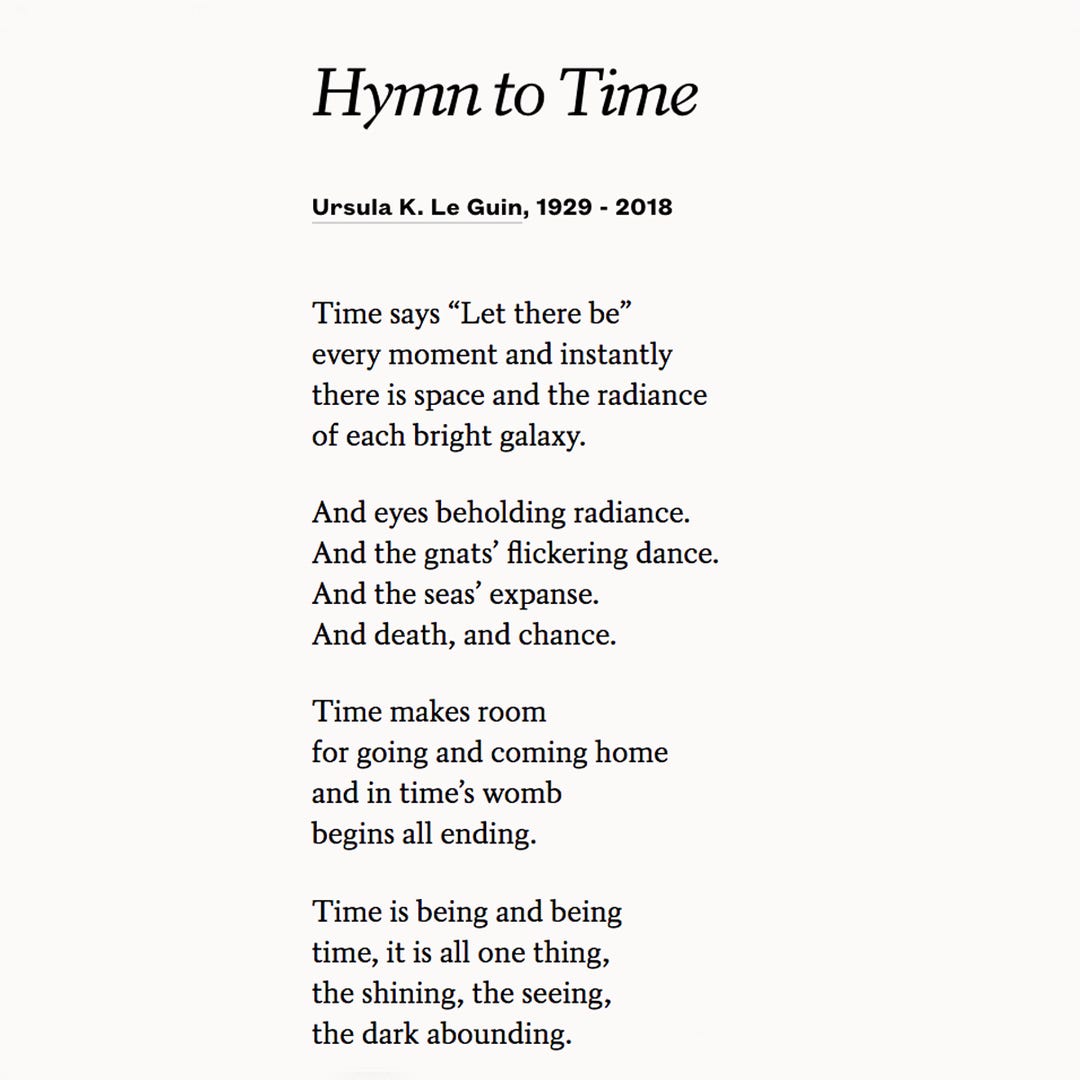

This poem by Le Guin was one of the seeds for this essay. I’ll leave it with you here. <3

Ogden, R. S. (2020). Time perception and social disorientation during the Covid-19 pandemic. PLOS ONE, 15(7), e0235871. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235871

Andersson, M. A., Froese, P., & Bó, B. B. (2023). Out of time, out of mind: Multifaceted time perceptions and mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Time & Society, 32(3), 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X231188786

Hoerl, C., Rudd, C., & McCormack, T. (2022). Thinking in and about time: A dual systems perspective on temporal cognition. Philosophical Psychology, 35(5), 817–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2020.1863356

Csíkszentmihályi, M. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

Zacks, J. M., Speer, N. K., Swallow, K. M., Braver, T. S., & Reynolds, J. R. (2007). Event perception: A mind-brain perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 273–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.273

Gaming is really an area that journalism needs to watch - and not just by making crossword sections.